https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/indias-5-trillion-economy-plans-looks-good-on-paper-but-it-needs-to-address-gaps-4180721.html

India’s $5 trillion-economy: great idea, but the deliverables are missing

RN Bhaskar – 8 July 2019

On paper, the government has great plans. It wants to focus on Make in India and propel the country to a $5 trillion economy within the next few years. It is a good rallying point. It is inspirational. But a closer look shows that notwithstanding all the grandstanding, some core pieces are missing.

The intent

The government wants to launch a scheme to invite global companies through a transparent competitive bidding to set up mega-manufacturing plants in sunrise and advanced technology areas such as Semi-conductor Fabrication (FAB), Solar Photo Voltaic cells, Lithium storage batteries, Solar electric charging infrastructure, Computer Servers, Laptops, etc. and provide them investment linked income tax exemptions under section 35 AD of the Income Tax Act, and other indirect tax benefits.

Go to the Economic Survey 2018-19. It too states that “To achieve the objective of becoming a USD 5 trillion economy by 2024-25, as laid down by the Prime Minister, India needs to sustain a real GDP growth rate of 8%. International experience, especially from high-growth East Asian economies, suggests that such growth can only be sustained by a “virtuous cycle” of savings, investment and exports catalysed and supported by a favourable demographic phase. “

The key word for all these plans is investment – especially private investment. It is this investment that will create jobs, drive demand, create capacity and generate wealth. But investment is not something India can bring to its territorial jurisdiction easily. India needs foreign direct investment (FDI) urgently, and lots of it. Since FDI, unlike portfolio investment, is long term patient capital, entrepreneurs and bankers like to examine proposals very carefully.

Two of the biggest risks investors pay most attention to are promoters and country. How much of a risk could a promoter himself involve. What is his credibility, and not merely credit rating. Credit ratings only talk of the ability to pay. More crucial is the intent to pay. Does the promoter stand up to this requirement? What is his track record in implementing projects successfully?

A similar exercise is done for the country into which investments are sought to be poured. Does the country respect the rule of law? Does it bring about laws with retrospective effect? And more crucially, how quickly can disputes be resolved? Even if the promoter passes the test, and if the country does not, investments can turn skittish, and shy away.

The three charts reproduced below explain the reasons for investments into India turning skittish.

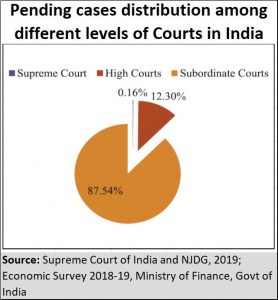

First, India’s record on the dispute resolution front has proved to be extremely worrying. That is why most investors prefer to insert a clause allowing for international arbitration from a seat outside of India (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/opinion-efficient-dispute-redressal-system-a-must-to-boost-fdi-3943071.html). This has been a requirement sought by investors ever since 2015 when the government sought to cancel all bilateral investment treaties. Instead it wanted countries to sign a new variant which had a clause stating that investors would not approach international arbitration centres outside of India till they had exhausted existing channels for dispute redressal within India. As might be expected none of the major investor countries signed the new format – excepting two Cambodia and Belarus.

India tried to assuage the fears of investors by setting up an arbitration centre in Mumbai. However, the government refused to guarantee investors that Indian courts would not be allowed to reopen an international arbitration award. This facility was provided by a five-member bench of the Supreme Court when arbitration awards were given by courts outside of India. Implicitly, any award given within India could be reopened by Indian courts. No investor wants that. Not surprisingly fresh investments for new projects have begun flagging.

The Economic Survey hints at this (see chart). The government has sought to increase the number of judges in the Supreme Court and the High Courts. But the backlog of cases in local courts continue to pile up. That is not comforting. In the past six months, key criminals have been let off because witness were either not traceable or had turned hostile – after the case had dragged on for 20 years or so. Does the government expect witnesses to agree to testifying before courts time and again for 20 years? Moreover, the biggest litigant in India is the government. Even the National Law Commission called it a compulsive litigant – a view ratified by the Supreme Court — http://sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2011/30837/30837_2011_Judgement_23-Nov-2017.pdf.

Are exports feasible?

The Economic Survey and the Union Budget 2019 both talks about the need to galvanise exports. But exports are possible when the global economy is growing and trade barriers are brought down. Currently both problems confront India and almost every other country.

Even if these factors can be faced, survival in the export markets depend on quality, reliability and competitiveness. Labour laws hinder significant gains on the first two fronts.

Even if these factors can be faced, survival in the export markets depend on quality, reliability and competitiveness. Labour laws hinder significant gains on the first two fronts.

The best case scenario for India will be to reduce imports and thus reduce the balance of payments. For this it has to look to affordable housing, (which it has begun taking seriously), rooftop solar (which has the potential for creating over 80 million jobs within a few years – http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/dear-pm-modi-heres-how-bureaucrats-are-planning-to-scuttle-your-rooftop-solar-employment-plans-2468501.html) and methanation – waste to energy, which could reduce LNG imports (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/05/transform-india-through-jobs-and-wealth-generation/). The government has yet to move quickly on the last two. Instead, the government has not even bothered to remove the crippling 25% safeguard duty slapped on solar imports. Quite unfortunate indeed.

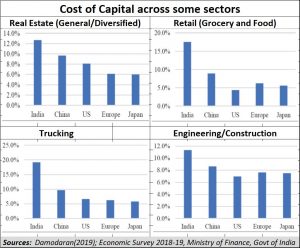

Exports from India are difficult for another reason. High costs (see chart) . India’s costs are the highest. Contributing factors to this high cost are inefficiencies in logistics, corruption at all levels, especially at the level of local administrators, and implementation inefficiencies.

With cost of capital being at least 25-30% higher than for other countries, Indian exporters are bound to be hobbled with this handicap. Current indications are that little action has been taken against local corruption.

Education and health

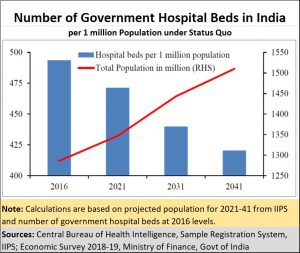

Finally, to push India to becoming a $5 trillion-economy requires investments in human capita(. India falters here as well (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/02/the-budget-does-not-care-for-human-capital/). This includes  investments in education and health. Yes, there is a new medical insurance scheme in Ayushman Bharat (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/opinion-ayushman-bharat-is-a-great-concept-but-where-are-the-doctors-2851461.html) , but the doctors are missing. Even the Economic Survey confirms this (see chart).

investments in education and health. Yes, there is a new medical insurance scheme in Ayushman Bharat (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/opinion-ayushman-bharat-is-a-great-concept-but-where-are-the-doctors-2851461.html) , but the doctors are missing. Even the Economic Survey confirms this (see chart).

The reasons there are few doctors, is because there are few seats in medical colleges. Domestic and global investors are willing to start medical education – and its corollary, medical tourism – but politically backed private medical colleges which charge capital fees of upto Rs.1 crore have not permitted the government to increase medical seats. Instead the government wants to promote Ayurveda and homeopath practitioners as full-fledged doctors (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/04/healthcare-requires-more-doctors-not-bridge-courses/). And this is where the rub lies. Students who have studied medicines overseas – often in better equipped and more competent institutes – are not allowed to practice in India, till they pass a certifying examination. But homeopaths and ayurved practiio9ners are not required to take the same test. The malaise afflicting medical education is true of almost all education in India.

If India wants to grow economically, it must first look after its human capital, it must focus on judicial redressal. It must ensure that investors’ fears of not having their investment protected are assuaged. In other words, it needs to revive international arbitration quickly.

Will India do this? Or will it continue dreaming about becoming a $ 5 trillion economy even as its foundations remain wobbly? The answers are blowing in the wind.

COMMENTS