https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/policy-watch-the-curse-of-being-an-abandoned-child-in-india

India’s callous and brutal approach towards the abandoned girl child

RN Bhaskar

In March 2021, India’s Enforcement Directorate (ED) took possession of a Rs 1.45 crore worth Delhi-based property belonging to Asha, wife of Brajesh Thakur, the main accused in Muzaffarpur shelter home sexual assault case. It also seized a fixed deposit of Rs 2.07 lakh.

The ED filed a criminal case of money laundering against Thakur, his family members, and others in October 2018 after learning of sexual abuse of minor girls at the shelter house run by Thakur’s NGO.

The seizures were laughable considering that, according to the ED (https://theprint.in/theprint-essential/twists-turns-in-muzaffarpur-shelter-home-sexual-abuse-case-and-its-political-impact/352728/), “Thakur and others diverted and siphoned off the funds/grants-in-aid (of about Rs 7.57 crore) received for the welfare of girl children and others and used the funds for their personal gain.”

Irregularly run CCIs

And why were the authorities pursuing smaller cases, when he was actually accused of a more serious crime – mass exploitation of female children residing at his ‘shelter’? Were the authorities trying to distract attention from the POCSO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012) matter?

And why were the authorities pursuing smaller cases, when he was actually accused of a more serious crime – mass exploitation of female children residing at his ‘shelter’? Were the authorities trying to distract attention from the POCSO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012) matter?

The Muzaffarpur shelter case, run by Thakur, is crucially important because it exposes the seamier side of politics, sex, and girl child molestation in India. So are two other cases explored here. All of them ended with convictions only because the Supreme Court stepped in. The legislature and the executive were either incapable or collusive.

It all began in June 2017 when Bihar’s Social Welfare Department asked the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, to prepare a report on the condition of shelters and short-stay homes in the state.

The report submitted in early 2018 revealed “physical and sexual violations of girls in Child Care Institutions (CCI) in India, many unlicensed, especially at the Muzaffarpur home.” The department then filed an FIR at the women’s police station in Muzaffarpur in May 2018.

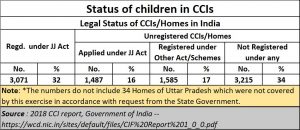

At the same time, the government of India too had been working on the state of CCIs across the country. It had been asked by the Supreme Court, in February 2013, to get this done (Writ Petition (CRL) No. 102 of 2007 in the matter of EXPLOI. OF CHILN. INJ ORPH IN ST. OF TN V/s Union of India & Ors). A committee was constituted by the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD — https://wcd.nic.in/) on 2nd May 2017. It submitted its report on 5 September 2018 (https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/CIF%20Report%201_0_0.pdf). This report finally made its way to the Supreme Court of India

In the meantime, the Bihar police stated in July 2018 that at least 34 girls were drugged and raped at the Muzaffarpur shelter home.

On 5 August 2018, Governor Satyapal Malik suspended (not dismissed) six assistant directors of the state Welfare Department for negligence in duty. Three days later, on 8 August, Bihar’s Minister of Welfare, Manju Verma, also resigned (her husband, Chandeshwar Verma, allegedly had links to Thakur). Within a fortnight, an FIR was registered against the Verma couple after 50 cartridges were found at their house.

In February 2019, a special POCSO court also ordered a CBI probe against Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar and two senior civil servants. The Patna High Court then took suo motu cognizance of the incident and decided to monitor the investigations.

On 29 August 2018, the high court also directed the Special Director, CBI, New Delhi to monitor the progress of the probe.

The Supreme Court steps in

In September 2018, the Supreme Court stepped in. The contents of the MWCD report became public knowledge. In February 2019, the apex court directed the case to be transferred from Bihar to POCSO court at Delhi’s Saket district court complex. It gave the CBI three months to complete the investigations. The CBI revealed lapses on the part of over 70 officials in Bihar, including 25 IAS officers, in managing shelter homes in the state. Whether – and how — they were penalised is not known.

The government officially informed the Supreme Court that India had 1,575 minors, who were victims of sexual abuse, and 189 victims of pornography. They were being ‘sheltered’ in the 9,589 childcare institutions (CCIs)across the country. There was a total of 9,382 children in such homes — 6,928 boys and 2,454 girls — in conflict with law. Almost 50% of the CCIs were without proper government authorisation.

“The number of children found to be victims of sexual abuses are 1,575 (girls-1,286 and boys-286) and victims of pornography to be 189 (girls-40 and boys-149),” the government told a bench headed by Justice Madan B Lokur.

In January 2020, the Delhi court convicted 19 persons, including main accused Brajesh Thakur. The judge convicted Thakur for aggravated sexual assault under POCSO Act and gang rape. The court acquitted one of the accused in the case.

However, the one state which refused to part with information for the report was Uttar Pradesh. It was in keeping with other acts of mismanagement that the state had indulged in. It had mismanaged finances (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/08/government-plunder-productive-states-in-india/), made a mockery of law and order (read more about the Unnao case below), and brazenly exploits farmers (https://www.moneylife.in/article/the-fight-is-no-longer-between-the-good-and-the-bad-but-between-the-corrupt-and-the-rapacious/62370.html). It opted not to disclose information on around 34 chile care institutions (CCI) in that state. Today, it refuses to disclose the number of Covid infected cases, and related deaths by now allowing extensive testing of potential cases (https://twitter.com/andymukherjee70/status/1383233764235517954?s=20).

But the MWCD too does not take child abuse seriously, it appears. After submitting the report in 2018, it does not seem to have followed up on regularisation of the CCIs, or getting inputs of how UP manages them. We asked the MWCD if the data from UP about sexual crimes and its CCIs had finally been compiled? Have irregular CCIs been regularised and suitably monitored? (https://twitter.com/rnbhaskar1/status/1383705744822833156?s=20) After all, almost 50% of the CCIs don’t even have proper registration. No reply was forthcoming. Evidently, even the ministry finds POCSO a hot potato.

Moreover, it is high time that the government, or the election commission, if not the MWCD, brings out a list of elected representatives charged with POCSO crimes. These are the worst of all crimes, and people must be made aware of the moral fibre of such elected representatives

In fact, in most POCSO cases, it is the Supreme Court, and not the lawmakers who have come to the rescue of brutalised children. The Muzaffarpur shelter case, the Hathras rape case, the Unnao tragedy, or the Jalgaon sex scandal. In each of them, the legislators and the executive were found wanting. The Supreme Court had to pull them up for dereliction of responsibility.

Unregulated and unrepentant

But then, India loves to make money by keeping organisations and businesses unregistered so that private graft can then be collected. This is the case with unlicensed hawkers, unlicensed businesses, illegal parking, irregular construction, even prostitution (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/01/maharashtras-specious-morality-sex-crimes/).The only party whom takes more money than the prostitute is the group in charge of enforcement of relevant laws.

The case of Uttar Pradesh is far more serious because it accounts for some of the worst atrocities against children (see chart).

The case of Uttar Pradesh is far more serious because it accounts for some of the worst atrocities against children (see chart).

Since UP sends the largest number of elected representatives to the parliament in India, it is not surprising that India too begins to reflect many of the repugnant practices of this state. It chooses not to provide information. It believes that votes matter, but that people are dispensable.

How else would you interpret elected representatives calling for election rallies (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2021/04/elections-show-contempt-for-pandemic-rules/) even after the election commission’s (EC’s) exhortations to ensure that the speakers and the audience wore masks and observed social distancing? How else do you explain the casual disdain safety when millions converged for the Ganga-snan (bath in the Ganges) during Kumbh Mela? It is only when there is a public uproar, that the government is prodded into action.

Ditto with the government’s unwillingness to spend more on education (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/08/the-national-education-policy-has-little-vision-less-strategy/) and improvement of health services (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/08/ayushman-bharat-great-concept-doctors-overlooked/).

True, Maharashtra has emerged as #1 in respect of crimes against children. But one reason could be that UP has become extremely adept in concealing information. Madhya Pradesh is also very notorious for crimes against children. But once again, going by the number of corruption cases against IAS officers in that state, it will not be surprising if numbers of crimes have been suppressed in this state as well. QED: the number of crimes against children may be much higher in UP and MP than reported to the NCRB.

In any case, as a media report pointed out, the trauma of rehabilitating these sexually exploited children is also daunting (https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/up-front/story/20180813-the-trauma-of-rehabilitation-1303846-2018-08-03). There is a plethora of laws meant to protect children and women. But each of these laws is so crafted, that it leads to further exploitation and abuse. Unless the enforcers of these laws can be prosecuted, the situation is unlikely to change.

Three problems

The issue of crimes against children has become more crucial because of three reasons.

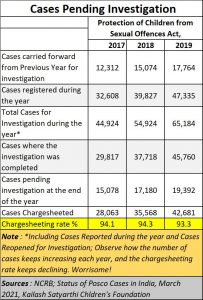

First, powerful vested interests in the government appear to be keen to go slow on POCSO cases despite the Supreme Court insisting that all POCSO cases should be finalised within six months.

First, powerful vested interests in the government appear to be keen to go slow on POCSO cases despite the Supreme Court insisting that all POCSO cases should be finalised within six months.

In December 2019, Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad wrote to all Chief Justices of all High Courts in the country (https://zeenews.india.com/tags/pocso-act.html). directing them to complete all cases of rape and those registered under the provisions of Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act within six months.

The words sound fine, till you realise that the government refuses to fill up the existing vacancies for judicial posts, even at the level of the Supreme Court (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2021/02/judiciarys-fabric-frayed-thanks-primarily-government/). Add to this the paucity of police officers as well and of forensic centres (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2021/03/jjudicial-and-the-extra-judicial-will-there-be-a-face-off/).

As a result, the backlog of cases in respect of crimes against children keeps climbing. The rate at which charge-sheets are filed also keeps dropping. If there is any single item that can underscore the callousness of India’s governance, it is the way the country deals with cases of child abuse and crimes against children.

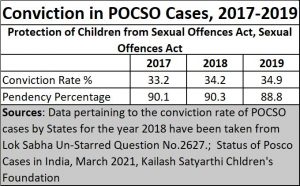

There is a second problem. Conviction rates are low. While the rate appears to be improving, the pace of improvement is extremely slow. People forget that at stake is the confidence of future generations that are supposed to build India and be proud of this country. The poor conviction rates only make people lose confidence in the law-and-order machinery.

But there is a third reason as well. It has much to do with the way a judge who pronounced the repugnant skin-to-skin judgement was reinstated (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2021/02/judiciarys-fabric-frayed-thanks-primarily-government/). This was an excellent case of non-application of mind, even incompetence. It had the potential for weakening the provisions of the stringent POCSO laws, aimed at protecting the child. The way the government – and the judiciary – allowed such a judge’s tenure to be extended is extremely disturbing.

But there is a third reason as well. It has much to do with the way a judge who pronounced the repugnant skin-to-skin judgement was reinstated (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2021/02/judiciarys-fabric-frayed-thanks-primarily-government/). This was an excellent case of non-application of mind, even incompetence. It had the potential for weakening the provisions of the stringent POCSO laws, aimed at protecting the child. The way the government – and the judiciary – allowed such a judge’s tenure to be extended is extremely disturbing.

And there are several indications that POCSO cases involving ministers and people close to powerful politicians are sought to be weakened. The case narrated above – the Muzaffarpur shelter case – is just one example.

Kathua, Unnao and fears

Take the Kathua rape incident. It relates to the badly brutalised dead body of an eight-year-old child belonging to the nomadic Muslim Bakarwal community. Her body was discovered in the Kathua district in January 2018. The biggest frustration came from crowds chanting slogans to challenge law enforcement officers from proceeding against the local priest who was the prime suspect (https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/kathua-rape-case-verdict-pathankot-court-update-1545751-2019-06-10). Finally, in May 2018 the Supreme Court stepped in and shifted the case from Kathua to Pathankot in Punjab. The case was fast-tracked and held in-camera, away from media gaze.

In June 2019, Sanji Ram, the caretaker of the temple where the crime took place, Special Police Officer Deepak Khajuria and Parvesh Kumar, a civilian, were convicted under Ranbir Penal Code sections pertaining to criminal conspiracy, murder, kidnapping, gangrape, destruction of evidence, drugging the victim and common intention. They have been sentenced to life imprisonment and fined Rs 1 lakh each for murder (https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/kathua-rape-murder-case-a-timeline-of-events-that-shook-the-nation-1545882-2019-06-10) . We do not know why the POCSO provisions were not applied.

The Unnao rape case was even more brazen – possibly because the accused was a politician. (https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/unnao-rape-victim-father-death-kuldeep-singh-sengar-convicted-1652295-2020-03-04). The principal accused was Kuldeep Singh Sengar — a BJP lawmaker (now expelled from the party),

He was accused of raping a minor girl in Unnao, Uttar Pradesh in 2017. Even while she was in the hospital, Sengar is alleged to have persuaded the police to file a false case against her father, possibly to pressurise her into changing her statement. When the father was out on bail, he got the father killed – the girl survived. In March 2020, the courts finally sentenced him for life for raping the child, and for culpable homicide and criminal conspiracy in her father’s death. Of the 11 accused, Kuldeep Sengar and six others have been convicted.

The manner in which the police was persuaded to look away from actual evidence and even fabricating evidence to implicate the father finally led to the case being transferred to Delhi on the Supreme Court’s directions in August 2019 from a trial court in Uttar Pradesh.

The girl has been given accommodation in Delhi and is under CRPF protection.

But the ironic twist in the case took place when it was revealed in April 2021 (https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/unnao-rape-accused-kuldeep-sengar-s-wife-picked-by-bjp-in-up-panchayat-polls-1788875-2021-04-09) that Sangeeta, Sangar’s wife, will be fighting the upcoming panchayat elections in UP on a BJP ticket.

This could be a sign of the times to come.

COMMENTS