https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/policy-watch-the-good-the-bad-and-the-positively-ugly-of-the-new-education-policy

National Education Policy: What about the teachers and the vision?

RN Bhaskar — 20 August, 2020 (This article appeared in two parts in the print ediiton — on 20 and 27 August)

Just glance through the main recommendations of the last education policy brought out by the Kothari Commission (1964-66) (https://www.academia.edu/30217361/RECOMMENDATIONS_OF_THE_KOTHARI_COMMISSION_EDUCATION_COMMISSION_1964_66). Then compare it with the National Education Policy (NEP) brought out recently by the government of India (https://www.mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English.pdf).

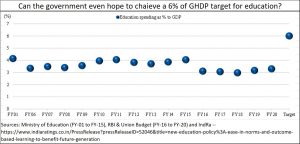

In both policies you will find the exhortation that more (6% of GDP) should be spent on education. Yet, the truth is that government after government has spent little on education. With little vision and less learning, India has tried to push through an NEP that has many similarities with the views of the Kothari Commission, but will less vision.

In both policies you will find the exhortation that more (6% of GDP) should be spent on education. Yet, the truth is that government after government has spent little on education. With little vision and less learning, India has tried to push through an NEP that has many similarities with the views of the Kothari Commission, but will less vision.

In 1964, when India was still struggling with basic necessities, the inability to spend was understandable. But today, when India talks about being a world power, this poor spending on education is scandalous, even criminal.

Worse, in the NEP of 2020, you will also find a bit of dogmatism, even prejudicial approaches. And you will also discover a great way to dream and fantasize. You could even call it hallucinate.

Consider for instance (see chart) that India’s ranking on the HCI or the Human Capital Index (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/05/poor-education-kills-million-of-children-each-year/). And then look at what the NEP’s faith in government spending. Touching indeed!

The good

Yes, the NEP has some very good parts.

It includes pre-school education into the main education structure. This allows for two things.

First, it seeks to regulate an unorganized, unregulated, and even profiteering part of education, sometimes with very unhealthy linkages to primary school admission in urban centres like Mumbai and Delhi.

Second, it allows for the mid-day meal being extended to preschool children right from the age of three. In a country where 50% of children are malnourished, this will be a big benefit. As any nutritionist knows, if proper nutrition is not provided to a child at the age of 3, brain development suffers. This measure alone will benefit millions of children across the country. But whether this will mean an upgradation of skills, certification, and salaries for the 1.2 million anganwadis remains to be seen.

Another good thing is the focus of the NEP on the all-round flexibility in course structures. But then this was suggested by the Kothari Commission as well. It talked about vocational courses even then. The 10+2+3 was devised so that children could opt for vocational course after the 10th standard examination. This author was on the sub-committee advising the Maharashtra State government on vocational courses, and it was distressing how these courses were sought to be taught at the +2 stage, in classrooms, without any exposure to workshops or fieldwork. There is no guarantee that this won’t happen again. True, the government has modified the 10+2+3 into 5+3+3+4. And it has introduced a credit system, which allows for more lateral migration between subjects and courses. It remains to be seen how the 1.5 million schools in India adapt to this new structure.

The bad

Then come some not so good parts.

The NEP is full of impressive phrases like holistic and multi-disciplinary. Yet scratch at the paint, and you can see signs of fundamentalism and prejudice.

Take the emphasis on foreign languages. Why bring politics into education? The NEP excludes Mandarin. This defies logic. Did the US ban the teaching of Russian during the cold war? Even if China is an enemy, it is good for Indians to learn Mandarin. To understand an enemy better. To understand Asian history. To explore business opportunities in a territory where China accounts for the world’s largest population.

Moreover, irrespective of whether an India works for a multinational corporation from the West, or from countries like South Korea or Japan, or whether he works for an Indian enterprise, knowledge of Mandarin would allow for better business negotiations. The NEP seeks to slam shut such doors for Indians and thus create employment opportunities for people from other nations. It is also true that while India and China have strained relations currently, both countries have peacefully coexisted for over 2,500 years. Wy confuse the long-term with the short-term and possibly transient?

The irony is that even while Chinese Universities encourage the learning of Indian languages, India prefers to do without such learning. That will give Chinese an edge over Indians in the global employment market. How chauvinistic and myopic can the makers of an education policy get?

Take another example. The Kothari Commission was emphatic that English should be the link language in higher education for academic work and intellectual inter-communication. Hindi could also be a link language. But it advocated a three-language approach. A focus on regional languages, any other language approved as an official language by the Union of India and a foreign language. There was no prescription or exclusion. The first draft of the NEP actually tried to make Hindi a compulsory language and backed off only in the face of stiff opposition from all the Southern States.

True, English is spoke only by a sliver of the population. Regional languages and Hindi account for a higher circulation when it comes to newspapers and magazines. But English is increasingly relevant for corporate and financial worlds – not just in India, but globally. That is why Germany insists on courses in English, as does China. That is why even housemaids want their children to study English. They know market realities which politicians choose to ignore. And don’\t even think of changing the language in Indian courts, because there are not enough precedents or case studies for fords in other languages. It will make judicial redress even more complicated than it is now.

Typically, India has not come to terms with the basic fact that – unlike the North – the South has enjoyed greater continuity of culture and amity. The Chola dynasty lasted over 1500 years. Yes, it waxed and waned, but it lasted longer than any northern dynasty. When it was large, it covered territories up to Malaysia and Indonesia. It was South India that brough gold in from territories controlled by Rome. Today, the South has temples which exude culture and learning. Yet, the politicians of North India appear to have got the upper hand, and have tried to re-write history, and learning.

Similarly, Indian schools have ignored the fact that the only two empires that withstood the Mughal invasion were the Marathas and the Ahom Dynasty (that ruled the North East for almost 600 years). But NEP appears to be promoting the Delhi culture, rather than talk about the immense strengths of a link language like English and the number of non-Delhi satraps that defeated foreign powers who sought to invade the territory called India.

The ugly

The first problem with the NEP is its ability to fantasize — even in the face of political and fiscal realities. It still hopes to spend 6% (see chart). This will require a major rethink in policy making. And till that is done, India cannot become a global power.

The first problem with the NEP is its ability to fantasize — even in the face of political and fiscal realities. It still hopes to spend 6% (see chart). This will require a major rethink in policy making. And till that is done, India cannot become a global power.

The second fantasy is that India will achieve a higher GER (Gross Enrolment Ratio). While higher education GER in India is on an increasing trend, it stills lags when compared with other countries. Globally, the GER is measured for higher education for ages 18-22 years. GER for India is only 30.6% (though quality is pathetic – http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/01/pre-budget-series-barbarians-at-the-gates-of-education/. Yes,  India’s GER is higher than Pakistan (9) and Bangladesh (21), but it is significantly less than China (51), South Korea (94), Malaysia (45), Indonesia (36), Iran (70) etc. Globally, developed countries which encourage vocational education also do extremely well – USA (higher education GER is 88), UK (60), Germany (70) and Canada (69) (https://factly.in/gross-enrolment-ratio-ger-of-higher-education-improves-but-challenges-remain%EF%BB%BF/). The NEP nurtures the fond hope that India’s GER could reach 50% (no mention about the quality of education) by 2030. Hah!

India’s GER is higher than Pakistan (9) and Bangladesh (21), but it is significantly less than China (51), South Korea (94), Malaysia (45), Indonesia (36), Iran (70) etc. Globally, developed countries which encourage vocational education also do extremely well – USA (higher education GER is 88), UK (60), Germany (70) and Canada (69) (https://factly.in/gross-enrolment-ratio-ger-of-higher-education-improves-but-challenges-remain%EF%BB%BF/). The NEP nurtures the fond hope that India’s GER could reach 50% (no mention about the quality of education) by 2030. Hah!

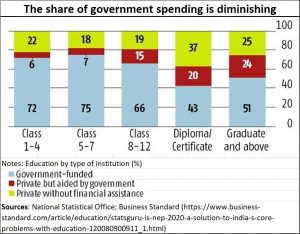

There is another reality that the NEP ignores. It is the ability of the government to quietly shift to the private sector the cost of education. This effectively means that more and more people are opting for private education. This is true even for Class VIII students who are supposed to get free-of-cost education, funded by the state.

There is another reality that the NEP ignores. It is the ability of the government to quietly shift to the private sector the cost of education. This effectively means that more and more people are opting for private education. This is true even for Class VIII students who are supposed to get free-of-cost education, funded by the state.

Just look at the enrolment numbers in government owned and municipal schools in India’s cities, and compare them with the increase in numbers in private schools. It tells you one thing.

Even children of casual workers prefer to go to private schools because the child learns more there than in government schools. It could be the teachers. It could be the environment, or it could be forcing children to learn in a language that their parents do not want. Policymakers should smell the coffee beans before writing out such fanciful reports.

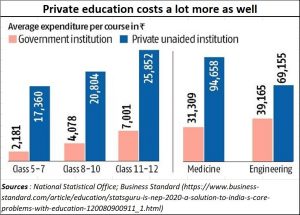

What is worse is that even while the share of the government in education is falling, the cost of private education has kept climbing, even to being extortionate (see chart).

Take a simple example. Ever since the government abolished the Medical Council of India, thousands of aspirational students have waited for the government to liberate the number of medical seats in the country. Yet this has not happened, even though India suffers from a paucity of doctors (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/05/atma-nirbhar-bharat-and-healthcare-headed-for-the-icu/).

The simplest solution would have been to allow existing government hospitals – which have land and are located at easily accessible areas – to grow vertically. They have the patients who stand for endless hours outside hospitals, which don’t have enough doctors. That would have collapsed the cost of medical education. Yet even this simple practical step is not being taken. Clearly, there are vested interests in government keen on profiteering from private medical education.

A similar situation can be found with schools as well. Try opening a school, and you will find that the compliances are so daunting, expensive and time consuming, that unless you have both the political clout and tenacity you will not start a private school.

The chart alongside shows the difference between the cost of education in government educational institutions and privately managed educational institutions.

The chart alongside shows the difference between the cost of education in government educational institutions and privately managed educational institutions.

What about teachers?

The worst part about the NEP is that it does not focus adequately on teachers.

Yes, there is a full section (Section 5) on teachers, but this deals mostly with upgrading teachers, testing teachers’ knowledge, and even attracting bright minds to the teaching profession. The NEP states: “To ensure that outstanding students enter the teaching profession – especially from rural areas – a large number of merit-based scholarships shall be instituted across the country for studying quality 4-year integrated B.Ed. programmes. In rural areas, special merit-based scholarships will be established that also include preferential employment in their local areas upon successful completion of their B.Ed. programmes.”

Giving students scholarships is fine, but how do you retain bright minds to continue teaching at schools? While the Kothari Commission did talk about upgrading salaries of teachers, and suggested norms for salaries, the NEP does not make any mention about paying higher salaries to good teachers.

It does not come to grips with the fact that a qualified teacher may not be a good teacher. Just like a good credit rating only tells you something about a person’s ability to pay, but not his intent to pay, passing teacher evaluation tests or B.Ed. courses only talks about a teacher’s ability, not his or her intent or effectiveness.

For this you must measure outcomes. The NEP is silent about this.

Eventually, education is all about a teacher. The better a teacher, the better does a student learn. An uninspiring teacher turns off students, and even cripples them mentally. That is why merit and outcomes matter. And for that salaries need to be revised to pay teachers who achieve the desired outcomes as much as the BFSI sector would pay.

It is only then that good talent will get attracted to and will stay with teaching.

However, even the private sector exploits teachers. This author – almost 30 years ago – was being paid Rs.200 an hour for teaching in private coaching classes (he had left full time teaching by then). That amount would be close to Rs.600-800 today. And the classroom size would seldom exceed 50 students. Yet look at what online educators do. According to one media source (https://the-ken.com/story/byjus-300-million-acquisition-whitehat-jr/) WhiteHat Jr — recently taken over by Byju for $300 million — has “three million students, 5,000 teachers and $150 million in an annual “run rate” in just two years . . . it pays teachers [a mere] Rs 275 ($3.7) per hour while charging students Rs 600 ($8) per hour.”

The government short-changes teachers, so why not the private sector too? It is doubtful if the best talent in teaching will remain with such entities.

It is also true that missionary teachers do exist, for whom money means nothing. That is how Christian schools have succeeded in getting the best teachers and education administrators. Missionaries help because they offer competence and passion at practically no cost.

But the church has succeeded because it has a longer-term perspective than politicians. Temples had this advantage too. That was how the educational institutes around the Tirupati Tirumala grew, till politicians nationalised Hindu temples and prevented them from carrying out the work that they had been doing for centuries.

If India wants to promote Hindu culture, and education through missionary zeal, please begin with liberating the temples from politicians and the government (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/09/entrepreneur-godmen-flourish-as-hindu-temple-trusts-nationalised/). The NEP stays away from this crucial area.

If the teacher is not looked after, merely giving a student scholarship will just not work.

Are there solutions?

Can India offer good education at reasonable costs?

The answer is yes. And it must begin with allowing educational institutes to raise funds and expanding to cash-rich areas – not just where the government wants them to go. Start with government owned educational institutions, and then permit private educational institutes as well.

Allow government hospitals to increase their intake of medical students at least ten times the current number. That should not take more than two years, because that is the time required to construct additional floors and equip halls with beds and equipment. If there is little money for medical equipment, ask the insurance regulator to get medical insurance companies to finance, and manage these additional beds and educational courses. Of all the institutions in India, the insurance sector has the money, the understanding of medicare costs, and the vision. Harness this sector into managing medical education. This will solve two problems. Quality education and decent health services.

Also allow educational institutions to pay teachers with good outcomes a salary at least four times more compared to what they get now. That will put pressure on non-performing teachers to improve or to quit. A teacher who does not show good outcomes for three years in a row should be asked to leave teaching.

And how will such higher salary costs be met? Two ways.

First, allow all government-owned institutions the right to admit foreign students from any country (including China, because money is money and cross-cultural influences can be extremely helpful). Charge foreign students five times the fees Indian students pay – much in the same way that Indian students pay a higher fee in foreign countries than what local citizens pay. Unless, of course, the foreign student is exceptionally good. In that case, offer scholarships, the way Singapore does. Good talent will benefit India in many ways.

Unfortunately, till recently, the government has not permitted Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) to open campuses overseas. Even IITs have been denied this right. Instead (under the ministership of the late Arjun Singh) even contributions from IIT students to their alma mater were sought to be impounded by the government.

Allow the renting out of classrooms for events over weekends and vacations, in such a manner that the contractor ensures that the place is not spoilt, and the funds go into government accounts meant strictly for education. And get the inspector raj out of education. Look at the bribes educational inspectors make by not clearing regularisation of teachers, or sanctioning schools the intake of additional students.

Finally, encourage more students to contribute to their alma maters in much the same way as IITs and IIMs do. If students are confident that the money will not go to the pockets of politicians or amorphous government funds, they will contribute. Any difference in funds requirement can then be made up by charging higher fees and through government grants.

A lot can be done in financing education. But that will happen only if the government has the vision and the wiliness. Mere targets for GER and government expenditure will not work. This approach has not worked in the past when India did not have the money. It will not work in the future if the government has little intent or vision to improve education.

Till that time, the NEP is merely a good story to tell people.

Go ahead, dream on. India has been fed on dreams before. But don’t blame the people if India’s global ranking continues to slip.

COMMENTS