https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/too-soon-to-celebrate-storm-clouds-ahead-for-india

Is the worst over for the Indian economy?

RN Bhaskar

Most speculators seem quite upbeat after the pounding they have gone through during the recent bear phase. They believe that good times have begun. Maybe, they are right. It does look so, especially if one looks at corporate performance.

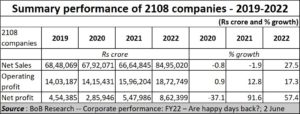

Summary results of 2108 companies studied and analyses by the research team of Bank of Baroda suggest that this is a good year. Corporate performance has been good in terms of sales and profits. So, obviously, nobody can blame marketmen for feeling euphoric.

But there are reasons to believe that this euphoria may not be long lasting, unless key policy decisions are taken. And there are good reasons for the scepticism.

But there are reasons to believe that this euphoria may not be long lasting, unless key policy decisions are taken. And there are good reasons for the scepticism.

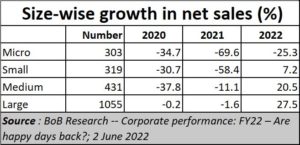

Just look at other sets of numbers. Take corporate performance by the size of the companies, for instance. You will discover that the best growth came from big players. Their sales grew by almost 28%. After two years of negative growth, a 27.5% growth in sales is certainly impressive. Several explanations have been offered. It could be that they could market their goods more effectively. Or they may have begun making a strong push into exports. Or maybe, they had hiked the price of their goods, and thus earned higher  profits. Maybe it could be a combination of the above. However, there is no denying that the big guys had enough cause for beaming smiles.

profits. Maybe it could be a combination of the above. However, there is no denying that the big guys had enough cause for beaming smiles.

But look at the smallest of players – the micro segment. Their performance was a mirror image of the growth by the big players. Their sales shrank by 25%. And while the market looks more at big players than small, it is the small players that actually move the economy, because of their sheer volume of numbers (https://asiaconverge.com/2018/11/please-leave-msme-interest-rates-alone/). They account for the highest employment in the country outside of agriculture, and also contribute significantly to the gross value added (GVA) of the economy.

When micro units do badly, they are the first to shed employees. This is because their ability to withstand a downturn is extremely fragile. They cannot take more risks that they have already. That in turn means fewer employment opportunities may be expected from this sector.

Many are still smarting from the wounds inflicted by a flawed implementation of GST on the one hand, and the old hammer blows of demonetization. For instance, GST still does not allow small players to get credit from hotel stays and expenses incurred while in another state where they may not be registered. Unlike big players who are registered in every state, small players seek registration in just one state. So, their ability to market their wares in states other than the home state becomes that much more difficult. For a country known for its IT skills, a few lines of computer code could have solved this problem. The GST is thus not the one-country-one-law measure that the government once promised (https://www.freepressjournal.in/interviews/one-nation-one-tax-tangled-in-complexity).

Then there is the inevitable corruption which appears to have become more rampant with each passing year (https://asiaconverge.com/2016/12/want-to-uproot-corruption/). . Small players endure the brunt of corruption more acutely than big players. And extortionists (mostly government employees) like to prey on the vulnerable.

The world of compliances too is extremely savage. It is not easy to do business when you are a small player in India (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/05/india-and-ease-of-doing-business/)

The vulnerability of small businesses, and the oft-heard stories about people losing their jobs, made Indians save a lot less than they ought to have. This was partly because there was little money  left to save, but also in some cases, a rebound into consumerism after two years of restrained purchases– thanks to the pandemic.

left to save, but also in some cases, a rebound into consumerism after two years of restrained purchases– thanks to the pandemic.

What is worrying about this shrinking level of savings is that most people preferred putting their money into fixed deposits rather than into financial instruments, points out Ishan Gera in Business Standard (https://businessstandard.substack.com/p/india-is-saving-without-gaining?s=r). This was probably because the small player is too scared of losing his shirt in financial markets. Hence, he prefers the deposit route even though — considering inflation – he was losing money on account of negative real rates of interest.

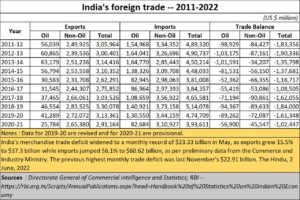

Finally, there is the spectre of global trade. Government spokespersons would like us to believe that the current turbulent times are on account of the Ukraine Russian war. That, they say, has caused a spike in grain, commodity, and energy prices. Yes, that is true. But only partly true. India has been slipping in global trade for a long time.

India’s trade balance has almost always been in the negative territory. Despite all the exhortations of Make-in-India, the country’s planners always seem to find a way to import when common sense suggests that imports should be shunned. The best example of such myopia is the way the country opted to import edible oils (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/01/the-government-lets-down-indias-edible-oil-industry/).

Moreover, as The Hindu pointed out on 2 June 2022 (https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/trade-deficit-widens-to-record-2333-bn/article65488487.ece), India’s merchandise trade deficit widened to a monthly record of $23.33 billion in May, as exports grew 15.5% to $37.3 billion while imports jumped 56.1% to $60.62 billion. The previous highest monthly  trade deficit was last November’s $22.91 billion.

trade deficit was last November’s $22.91 billion.

The government’s high-handed ban on steel (and wheat) imports points to the insensitivity with which the government views exporters and importers. The unleashing of enforcement officials to hound people who have indulged in financial transactions – sometimes more than a decade ago – has only made genuine exporters shrink into their shells. The general rule should be not to hound people, till there is definite proof. The present culture appears to be to lock up people first, and search for evidence later. That is not very conducive to a business-friendly regime.

The good news is that the government is beginning to heed to such muted protests. But the sad news is that data, on the basis of which business decisions get taken, is becoming more difficult to access. The government’s move to dispense with the statistical supplement to the Economic Survey this year is a good example of how the government wants businesses to operate without decent data inputs.

All this can be remedied. But India’s policy makers should wake up and work towards making the country a friendlier place to do business in, and thus to generate more prosperity.

COMMENTS