Can India grow to #3 in the world by 2028?

RN Bhaskar

Last week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India would become the third largest economy in the world by the end of his third term (https://indianexpress.com/article/india/pm-modi-india-worlds-top-3-economies-third-term-8862006/). He said he would guarantee this.. Elections are due in 2024, and should Modi win again (there is no reason to believe he won’t), his third term would end in 2028. Can India grow the way the prime minister has predicted?

One is not sure. And there are three reasons for this. First, growth depends on several variables. The government may be able to control one or two, but not all.

One is not sure. And there are three reasons for this. First, growth depends on several variables. The government may be able to control one or two, but not all.

Second, there are caveats.

Third, the environment for doing business must improve significantly.

Playing with the numbers

But since the prime minister has made this prediction, this author has attempted to crunch some numbers.

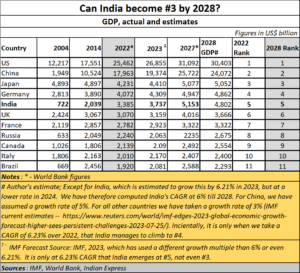

Take the chart above. Is based on actual GDP numbers given out by the World Bank for 2022. The figures are in billion US dollars. In 2022, India ranked No. 5.

One way of predicting the future is by considering past performance. Another is by taking the predictions of organisations like the IMF at face value.

Since the IMF expects the world to grow at around 3% y-o-y, we have applied that compounded rate of growth for most countries. The only exceptions for the purposes of this table are India and China.

Change this rate-of-growth number and the results will be different. If the UK were to grow at 8%, compounded till 2028 (highly unlikely), it could trounce India and become larger than India, in terms of GDP.

We have assumed India’s GDP growth at 6%, because it is unlikely to grow faster given India’s track record during the last two terms of the current government. And we have kept China’s GDP at 5% because it is most likely to achieve this rate of growth (notwithstanding sceptics from the west).

The results show that India will still remain #5 in 2028. Of course, if India grows faster at a compounded rate of 6.23% y-o-y till 2028, and if everything else remains the same, it could then become No.4.

But as stated before, all these are hypothetical numbers. Just look at the predictions of the IMF and the way it has constantly modified India’s projected rates of growth.

But as stated before, all these are hypothetical numbers. Just look at the predictions of the IMF and the way it has constantly modified India’s projected rates of growth.

However, if the past is anything to go by, India’s GDP growth rates have not been impressive in the recent past. It did boast of higher growth rates of 8.3% and 7% in 2016 and 2017. But it has slipped thereafter. Even the brief lead of 11% was only to make up for the negative growth of 10% the previous year. When adjusted against this negative number, actual GDP growth in 2021 was just 0.11%.

If the recent past has been unimpressive, can the future be different?

The future can be bright

Yes, the future can be bright. Economists working with the Reserve Bank of India believe that India can grow much faster (See the chapter ‘India @ 100’ in the July 2023 edition of RBI’s Monthly Bulletin — https://rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_ViewBulletin.aspx). The authors say, “India could become a developed country by 2047 with an average annual real GDP growth of 7.6 per cent sustained over the next 25 years. Analysis presented in this article shows that it is feasible.”

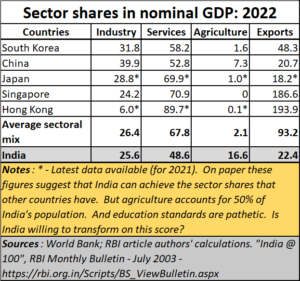

But the authors add some key caveats, put across quite subtly. They say that it is indeed possible provided the country is powered by

- The growth augmenting impact of policy focus on structural reforms, investments, logistics and digitalisation of the economy,

- upskilling the labour force to reap the potential of favourable demography, and

- sectoral policy initiatives covering manufacturing, exports, tourism, education, and health.

And that is where the rub lies.

The biggest pitfall confronting India is its inability to provide decent primary education to its teeming children (free subscription — https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/the-state-of-education-in-india). India has to its credit – according to the statements the government has made before the Parliament in the recent past –

- A terribly low GER of just 27.3.

- 1,17,285 schools with just one teacher for all subjects, all classes, as on 27 March 2023.

- Only 14% of government schools with functional internet connected smart educational facilities.

- And, 52% of its schools without science laboratories.

This is without considering the disastrous quality of education imparted to students in Indian schools. Take for instance the ASER report compiled by Pratham (an NGO focussed on education). In 2018, for instance, Pratham’s ASER reports showed that only 44.2% of the children in Std V could read the books meant for Std II. The score had declined from 53.1% in 2008 (https://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202018/Release%20Material./aserreport2018.pdf).

These poorly educated children are promoted through state mandated grace marks. Many of them then become eligible to go in for college education, without having the basic skills that college-going students must have.

These poorly educated children are promoted through state mandated grace marks. Many of them then become eligible to go in for college education, without having the basic skills that college-going students must have.

No wonder then, large employers like McKinsey and TCS consider barely 30% of the graduate population as being employable for jobs meant for graduates. Many of ‘unemployables’ eventually end up becoming attendants in shopping malls, or courier delivery personnel. But they are unhappy with their jobs because they believe that since they are graduates, they deserve a lot more.

A similar issue confronts India when it comes to reservations in higher education (free substack subscription — https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/the-state-of-higher-education-in?sd=pf). Just last week, the government admitted that over 11,000 students who got into Central Government Universities through the reservation route opted out of their studies (https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2023/mar/29/over-11k-obc-sc-and-st-students-dropped-out-from-central-universities-in-five-years-centre-2560686.html).

That prevented other deserving students from getting admissions to these institutions, and demoralised the enrolled ‘reserved’ candidates. This needs to change for education and even employment. India cannot afford to have key customer interface positions being manned by people not qualified and do not have the aptitude for the job. Ideally, the government should provide scholarships and additional facilities at the school level itself, upgrade the skills and learning of the underprivileged, and not have any reservations post-high-school. But politically, the government will not do this. That can handicap the country’s future growth.

A similar crisis confronts India’s healthcare as well (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/11/no-atma-nirbharta-without-healthcare/). If these are not ameliorated, India will not be able to reap the bonanza from its demographics.

Capex woes

All these, plus a flight of capital and high networth individuals (HNIs) from India (free subscription – https://bhaskarrn.substack.com/p/earlier-it-was-diamonds-will-it-now?sd=pf), have muddied the investment climate. That will slow down capex, which in turn will slow down India’s growth. The present PLI threatens to bring in the licence raj once again (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/10/pli-and-the-indian-economy/).

The crisis in agriculture is even worse, with the brightest children moving to cities. They prefer leaving management of the farm to siblings who are not the brightest. As a result, it becomes difficult to bring in technology into an area which has been largely abandoned by the brightest.

The crisis in agriculture is even worse, with the brightest children moving to cities. They prefer leaving management of the farm to siblings who are not the brightest. As a result, it becomes difficult to bring in technology into an area which has been largely abandoned by the brightest.

The cities seduce the youth, yes. But the government too drives them away from villages. Its decision to control dairy cooperatives (https://asiaconverge.com/2023/01/sodhis-resignation-has-dire-warnings-for-agriculture-and-milk/), ban commodities future trades in several crops (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/10/the-folly-of-banning-futures-trading-in-commodities/) and its eagerness to pander to rural populations with free food, free toilets and the like (https://asiaconverge.com/2023/07/eliminating-poverty-the-india-way/), instead of education, is breeding a generation which will be habituated to living on doles.

Investments in workforce

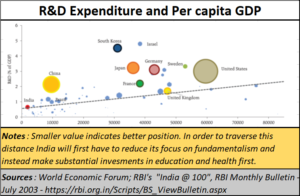

That in turn results in poor investments in workers. India’s investment on workers is among the lowest. Yes, there is a surge in such investment, growing almost five times since 1980.

But when compared with other countries, India’s workers do not match up. Further investments are required. Whether India will be able to make it remains to be seen.

It is quite possible that some economists may say that even the meagre investments when multiplied by India’s demographic dividend could yield impressive results. But they forget a crucial factor – education. Without education, even skill development can become a challenge.

The paucity of investments on workers, and on education and healthcare, eventually shows up as very low investments in research and development on the one hand and per capita income on the other. Look at Bangladesh. Its investments in school education are beginning to pay off. And its per capita GDP has climbed higher than that of India (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/05/bangladesh-trounces-india/).

The incentive to invest is further hampered by tax laws like the recent 28% GST on casinos (https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/tax-on-online-gaming-online-gamblinggst-public-gambling-act-8860106/) and the tax collected at source on foreign exchange spent through credit cards (https://indianexpress.com/article/business/incidental-expenses-on-education-health-fall-under-lrs-to-attract-tcs-8695115/).

The government’s urgent need for additional funds is understandable. It has created a machinery to give out doles and grants, and thus needs more and even more money.

It could get this money easily if industry and the economy were to grow. But their growth has been stunted. Higher levels of tax will hobble the country further.

All this collectively makes for an explosive mix which will hobble India. Poor investments in education and healthcare, loosely drafted laws, raids and seizures on the wealth generators in India, and poor capital formation (thanks also to slowing of foreign direct investments), do not augur well. They make predictions about a glorious future for India a chimera.

COMMENTS