India talks of growth, but it will continue shrinking unless . . .

By RN Bhaskar

It is when you look at the sustainability of economic growth that you realise that India could be shrinking.

Except for the super wealthy, the rest of India is shrinking

Except for the super wealthy, the rest of India is shrinking

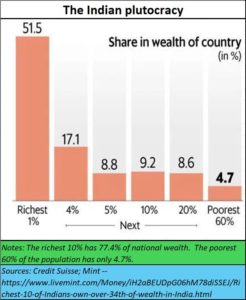

The only segment that is growing merrily is the top 5% which has been growing both in terms of wealth and numbers (https://www.livemint.com/Money/iH2aBEUDpG06hM78diSSEJ/Richest-10-of-Indians-own-over-34th-of-wealth-in-India.html). As far as other segments go, the numbers in each of those segments may be growing. But their quality of life, and the per capita incomes are under huge strain. The worst off is the bottom 60% of the population which has just 4.7% of the national wealth.

The middle class is the worst hit. It is not eligible for the freebies the government gives to the not-so-rich, and it cannot afford rising costs, which do not affect the rich. They also pay taxes. Not surprisingly, this segment is likely to shrink in percentage terms.

If this is not bad enough, many of the jobs in the service sector could be at risk (https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Jobs_of_Tomorrow_Generative_AI_2023.pdf). And do remember that the service sector accounts for a good part of India’s GDP, and employment. This sector covers all sorts of non-manufacturing jobs – for courier services, to retail sales, to accountants and even low-level code writers and IT professionals.

With very little focus on primary education (https://www.livemint.com/budget/budget-2024-strengthening-primary-education-through-nep-anganwadis-and-nipun-initiatives-for-school-children-11719206071486.html), even the quality of students coming out from schools is largely sub-standard, ill-equipped for jobs. They are unemployable. Hence many of the people who lose jobs may not find a new job easily because they lack the basic skills to allow them to migrate to better quality jobs meant for better skilled people. There will be jobs, yes. But they won’t be filled up by a large segment of the people who won’t be found fit for employment (https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/the-ecstasy-and-agony-about-the-indian?r=ni0hb&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&triedRedirect=true).

That in turn will reduce consumption demand, and even household savings. That consequently will reduce the government’s tax revenue. And that in turn will push the government towards more debt, or clever ways to window dress the deficit, like the largest ever dividend transfer from the RBI to the government or from banks and PSUs (Free subscription — https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/rbi-seeks-to-conceal-govt-deficit?sd=pf).

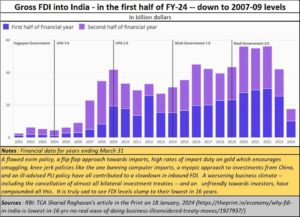

Clearly, India will have to work at a furious pace to fetch in foreign direct investments (FDI).

India needs the FDI is significantly larger dollops, because of several reasons.

It needs to create jobs, which can happen only with more investment and capital allocation.

Private domestic investment in creating jobs is declining, because many high networth individuals have opted to leave India (https://www.telegraphindia.com/business/35000-high-net-worth-entrepreneurs-left-india-during-narendra-modi-regime-amit-mitra/cid/1835449). Moreover, the raging returns on the stock markets have also caused funds to get diverted there.

Entrepreneurs find the investment climate too risky, and the government’s own compliances burden too heavy to shoulder. Add to that the danger of draconian laws being used by the government to put businessmen behind bars (https://asiaconverge.com/2024/05/fantasies-about-indias-economy-might-be-dangerous/). The uproar against criminalization of three additional laws (https://thewire.in/law/the-three-criminal-law-bills-using-criminal-law-to-establish-permanent-extra-constitutional-emergency-powers) is one more pointer at their discomfiture

Therefore, the need for FDI becomes even more crucial. But even this appears to be eluding India. Why? A look at the sources from where FDI comes into India will reveal that much of it comes from either Singapore or the Netherlands. Probe a bit deeper and you realise that this is because these two countries still allow for international arbitration which protects investments made through these countries. It was possibly the need to have the protection of international arbitration guaranteed under the bilateral investment treaties (BITs) between India and these countries that made even a company like IKEA choose to make its investment through the Netherlands rather than from its home country, Sweden. India’s unfortunate decision to cancel all BITs in 2014 has frightened away most investors (https://asiaconverge.com/2020/01/arbitration-and-investment-protection/). They know that India’s courts are too complex and time-consuming to cope with. In the event of a dispute, they need quick resolution. This is what the government does not permit, and does not like. That is the key reason why most countries do not want to invest in India.

True, foreign investment has been pouring into India for investments in deposits, government bonds, debt, and the stock markets. As a result, the country has money, its forex reserves are going up, but banks face a paucity of good borrowers. And the coming elections could even threaten government owned banks should state governments announce a loan waiver (https://www.livemint.com/market/stock-market-news/with-6-states-going-into-elections-farm-loan-waivers-pose-increased-risk-to-psu-banks-and-mfis-report-11721284073952.html) – more on this below.

If Indian needs foreign investment for capital formation, the government must make the country more investor friendly, with recourse to international arbitration. But that would reduce the power it wields over businesspeople through its enforcement and revenue officials. The clash between the desire for power, and the need for investment, is one that must be resolved, or India will continue to shrink.

Without investments, India’s goose may well get cooked, especially if service jobs get slashed in the Middle East as well, thanks to artificial intelligence (AI).

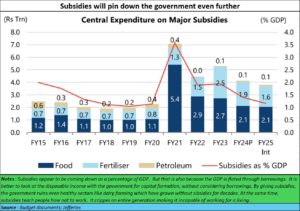

What will hurt India more is its willingness to promote gravy trains. When the Modi government came to power, it decided to disallow all states from giving loan waivers to farmers for money borrowed from banks. But when elections in Uttar Pradesh were to be announced, the government opened the subsidy tap. Loan waivers were allowed once again. Since then, the centre and the states have been trying to outdo each other in offering sops to people.

True, the percentage of subsidies (to GDP) appears to be declining. But that can be misleading. India’s GDP has been inflated (do read this brilliant article by Josh Felman and Arvind Subramanian at https://www.business-standard.com/economy/news/union-budget-2024-25-three-macro-puzzles-and-policy-implications-124071901345_1.html). Some of this inflation is through borowings and by expenditure on infrastructure at highly inflated costs, and with a lot of the allocations witnessing time and cost overruns. As one media report (https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/infrastructure/as-many-as-431-infrastructure-projects-show-cost-overrun-of-rs-4-82-lakh-crore-in-december/articleshow/107199310.cms?from=mdr) puts it, “A total of 431 infrastructure projects in India, with investments of over Rs 150 crore each, experienced cost overruns of more than Rs 4.82 lakh crore in December 2023, according to a report by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Out of 1,820 projects, 848 were delayed.” Moreover, as the bridge collapses and leakages around the country suggest, even the quality of such infrastructure is now suspect.

Subsidies are bad for India for several reasons.

They have been given to sectors which have managed to thrive without any subsidy support. A good example is the dairy sector, which was fine-tuned by Verghese Kurien (Free subscription — https://open.substack.com/pub/bhaskarr/p/kuriens-amul-can-legends-be-erased?r=ni0hb&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true). He showed the country — and the world — a way to make India the largest producer of milk and at the lowest costs. Yet, in a bid to break the relative autonomy of this industry, the government began dishing out doles selectively to milk producers. That in turn rewarded the inefficient, and penalized the efficient. It was a surefire way of making India uncompetitive and poorer. Another case in point is the way cattle slaughter laws have hurt the farmer and the Indian economy (https://asiaconverge.com/2023/01/sodhis-resignation-has-dire-warnings-for-agriculture-and-milk/). Subsidies and bad policy making have hobbled agriculture.

Another form of subsidies is the penchant to announce loan waivers. Already there are fears that the six states which go for elections shortly will announce loan waivers in an attempt to get votes (https://www.livemint.com/market/stock-market-news/with-6-states-going-into-elections-farm-loan-waivers-pose-increased-risk-to-psu-banks-and-mfis-report-11721284073952.html). That could hurt bank loan portfolios badly. This is particularly true of government owned banks, which are required to fund agriculture even with little collateral. Private banks prefer to transfer such risks to intermediaries – the non-banking finance companies or NBFCs). Since they bear a higher risk, they charge a higher rate of interest. But populism makes the government hound them for charging such higher rates. It has become a no-win situation.

The most worrying part about subsidies is that they teach people not to work, especially if given year after year. The government has announced that oof subsidies will continue for another five years (https://www.freepressjournal.in/indore/free-ration-scheme-will-be-extended-for-five-years-says-pm-modi-in-poll-bound-chhattistgarh-madhya-pradesh).

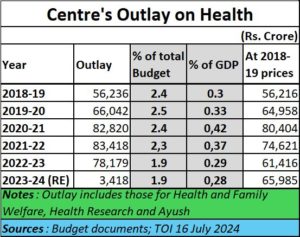

If the state of education is bad, just look at what is happening to healthcare. Almost 80% of patients depend on government hospitals which treat patients shabbily. Look at the serpentine queues outside hospitals. There are few hospitals and fewer doctors. Expenditure on healthcare has been an eyesore.

True the government has introduced a very impressive scheme for healthcare called Ayushman Bhava (may you always stay healthy). But there are few doctors who can carry out even a fraction of the targets that this scheme is meant to deliver (https://asiaconverge.com/2018/08/ayushman-bharat-great-concept-doctors-overlooked/).

Finally look at India’s exports and imports. The figures on India’s external trade front are extremely worrisome.

Year after India, India has had a negative trade balance (https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/fantasies-about-indias-economy-might?r=ni0hb&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&triedRedirect=true).

What the figures do not reveal is the government’s shortsightedness by creating rules that have hurt India. A good example is how the government almost allowed the import of dairy products from New Zealand, when every expert could have told the authorities that this would grievously maim India. It was only after almost 10 crore milk producers threatened to launch an agitation that the move was shelved (https://asiaconverge.com/2019/08/indian-bureaucrats-almost-shortsold-the-milk-industry-at-fta-cpec-negotiations/).

Another example is the way it has introduced high import tariffs on gold. Consequently, the country continues to import some 70-100 tonnes of gold annually. But only 3-5 tonnes of gold gets seized ty authorities. The remaining gold is paid for through unofficial means, thus eroding the value of the rupee, and hurting all exporters and importers (read the gold smuggling series https://asiaconverge.com/2020/10/gold-smuggling-i-is-encouraged-by-flawed-government-policies/). Given India’s well documented prowess in earning gold through thousands of years (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibJJXeGyZxA&t=33s), the government needs to look at this trade with admiration, not suspicion.

Yet another example is the way the government has encouraged edible oil imports.

A fourth example is the shortsighted way the government blocked telecommunications imports from China, leaving Indian players to opt for more expensive imports from the West. It could have learnt a lot from Vietnam and Singapore (Free subscription — https://open.substack.com/pub/bhaskarr/p/is-india-spooked-by-china?r=ni0hb&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcome=true). They ensure that there are at least two to three players encouraged in the market so that the country gets the best technologies and solutions at the lowest price. Similarly, India banned Chinese investments in Indian startups, even though many of the startups were funded by Chinese. Effectively, India blunted India’s own potential for wealth generation and even exports.

The list is long but if the government begins by focussing on ways to make India an attractive destination for FDI, and stops importing products that Indian farmers themselves can grow, they would be good starting points. A long-term policy which ensures that businessmen feel confident (no laws applied retrospectively please!) would help India grow, instead of shrinking.

=========================

Do watch my podcast on this very subject at https://youtu.be/FYtUsZVPlKU?si=brHyc8DMENExE8vN

COMMENTS